Negative Gaming Experiences, Expectations, and Disengagement

A layperson-friendly summary of a recent interview study about negative experiences in games, player expectations, and (dis)engagement.

Introduction

[Note: The contents of this blog post are available in even further abbreviated form by checking out the slides I used to present this paper at the 2022 IGGI Conference.]

After over a year of painstaking progress, I’ve finally completed a study about certain types of frustrating experiences in games, and how they affect players’ experience and behavior. The full paper is available on PsyArXiv as a preprint while it undergoes peer review, but in the meantime I wanted to make a shorter summary available as a blog post.

The study’s goal was to understand when and why need frustration—experiences such as failure, loneliness, or coercion—arises in video games, and what it has on players’ behavior.

We found some really interesting things—need frustration is common in games, and it has important impacts on players’ decisions to continue playing a game or not, as well as the emotional experiences they have when they play. We show that this happens through the violation of expectations about a game, an idea that hasn’t appeared very much in the research literature on games yet. Perhaps most interestingly, our results hint that need frustration may be a useful way to differentiate “positive”, motivating frustration from “negative”, demotivating frustration—a distinction most players and designers are familiar with.

What is need frustration in games?

Need frustration is an idea built upon a well-known and well-evidenced psychological theory known as self-determination theory. One claim this theory makes is that humans have innate and universal basic needs for1:

- Autonomy: the need to feel that one is in control over their own life and that one’s actions are self-endorsed

- Competence: the need to act effectively and feel capable in one’s activities

- Relatedness: the need to love and care, to be loved and cared for; to have one’s “true self” accepted by others and feel part of groups

When these needs are satisfied by an activity, people tend to enjoy the things they do, do them more, and feel better after doing them. On the other hand, when they are actively frustrated, people tend to enjoy them less, do them less, and feel worse after doing them.

In the table below, I’ve given some examples of need-satisfying and need-frustrating experiences in games. We know that games are really good at satisfying needs, generally; this is precisely why they’re so intrinsically motivating. But this is not universal: at other times, games can be very frustrating and demotivating. While we know that need-frustrating experiences are part of gaming too, we don’t know what they look like—when they occur, how people feel when they happen, and how they affect motivation. (Spoiler: I’m only able to give these examples because we’ve now done the study!)

| Need | Example of satisfying experience | Example of frustrating experience | |

|---|---|---|---|

| autonomy | selecting an avatar that closely matches your desired in-game representation | feeling forced to log in daily to receive a reward that may expire | |

| competence | overcoming a difficult boss after learning its attack patterns | playing against opponents so good, you feel it doesn’t matter what you do | |

| relatedness | connecting deeply with a particular character’s story | being harassed by other players for low performance |

What we did

We decided to address this by interviewing players about their experiences. We conducted and transcribed a total of 12 interviews, and used a method called grounded theory to develop a working model of how need frustration occurred and what consequences it had for players. The goal, and indeed hardest part about using grounded theory, is to constant challenge the model and try to “break” it—in this method, you choose whom to interview one person at a time and keep updating your list of questions, so that you can generate the data that would be most likely to either enrich or contradict your ideas.

We interviewed a total of 12 players from 8 different countries who each played a variety of different games, and who included a variety of ages, genders, and relationships to gaming. Each interview lasted about an hour.

What we found

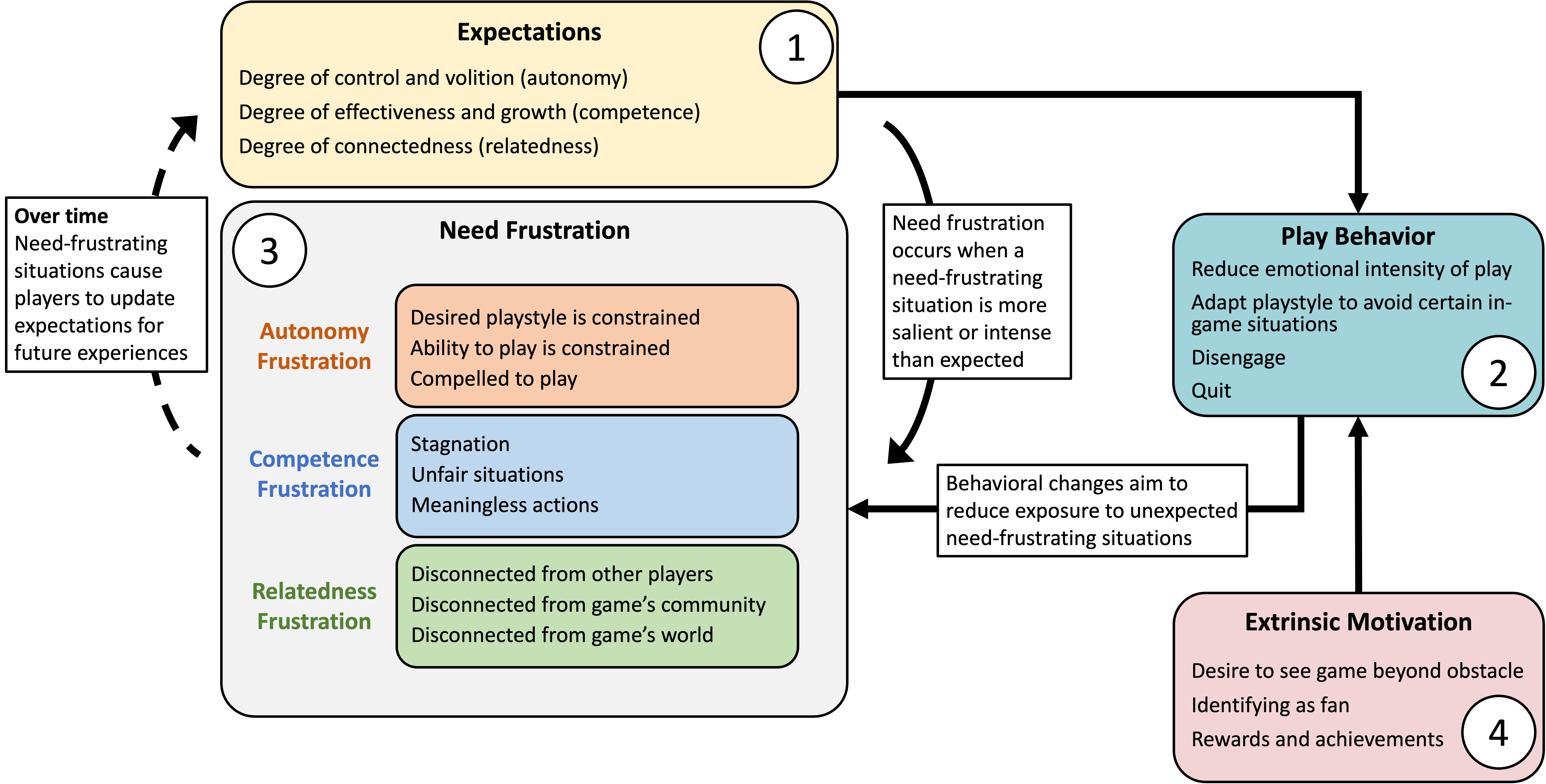

Below is the visual summary of the model we came up with.

The diagram has too many components for me to describe them all here—every line in the figure needs to be supported by multiple quotes from participants. I’ll first summarize the need-frustrating situations; while we found three categories of need-frustrating situations for each basic need, for space reasons I’ll just highlight one. Afterwards, I’ll discuss player expectations and how these lead people to change their behavior.

Autonomy Frustration

One of the most common types of autonomy-frustrating experiences is having one’s desired playstyle constrained. In other words, something prevented players from playing how they wanted to play at that moment—e.g., playing a particular character, using particular equipment or abilities, or taking certain in-game decisions. Constraints could arise from other players (for example, having one’s favorite champion or role taken in Overwatch), or from the game itself. One player wrote about how the game took her through a section of a storyline that she didn’t want to be part of:

Nowadays in [Assassin’s Creed games], when you are pulled out the Animus, it’s by force. And they then sort of force you to just do a few sort of mundane actions in the real world […] And I’m just like ‘why are you making me do this? I don’t want to do this, just can I go back in the Animus, please? That’s why I’m interested.’

Competence Frustration

For competence frustration, many players described situations of stagnation. This refers to a feeling of being unable to complete a desired or required action, and therefore being unable to progress. Progression doesn’t just refer to completing the goals that the game provides you, but also one’s personal sense of skill or advancement. This player provides a clear example of this when having a bad day in a multiplayer game:

I’m like ‘I can play this game, I know how to play it’ but, for whatever reason, every game I go into I just- I can barely get a kill. And I’m just constantly, you know, lowest on the leaderboard and in those moments I do, I feel frustrated at myself. And a little frustrated at the game, because I’m just like ‘I can do this, why can’t I do it now.’

Relatedness frustration

Being disconnected from other players arose when players had disagreements with their teammates, felt that a skill mismatch made for unequal in-game status, and—most commonly—when players were harassed by other players:

As soon as anybody finds out you’re a female gamer [in Call of Duty], it’s sort of immediately like, you know, just preconceived jokes. […] So it kind of makes it hard to feel included, even on your own team in those scenarios.

Expectations

Need frustration was experienced as “relative” to players’ expectations. Sometimes, players knew a need-frustrating situation might be coming up, and anticipating this meant that they were less affected by it. One player describes this in the context of lacking Black representation in avatar customization:

The best thing they’ve been able to do is change the skin color and maybe the hair, which is not even still close enough. You can’t really style it and stuff. I guess it doesn’t make me frustrated again because it’s expected, it’s not ‘oh, really, I’m so heartbroken.’ No, it’s expected. I expected it from the beginning. But if they do have it in the game, I’ll be more encouraged to play or buy.

Need frustration was therefore a result of unexpected (or unexpectedly intense) need-frustrating situations. This player nicely describes how the violation of their expectations resulted in a negative experience:

[Losing items irretrievably in \textit{Valheim}] definitely blindsided me […] I should have expected it and anticipated it, but I think I was just sort of so in the zone and kind of enjoying the whole experience and the learning and the things that I gathered and how far it progressed. I think that’s what made it more upsetting when it did happen and I knew there was no chance of retrieval at that point.

When players experienced need frustration, it wasn’t necessarily the case that they would immediately have a strong emotional reaction, or ‘ragequit’. Instead, what they reported was changing their expectations for the next time they played. This is nicely described by one of our players:

So if I found that, like, two hour process of beating a boss in \textit{Elden Ring} frustrating, and I really didn’t enjoy it, then I’ll be thinking ‘well I’ve played this one, so I don’t have to feel like I was beaten by it, but do I want more of that? Do I want to have to go through that process again and again to clear this game? And will I enjoy that?’ And sometimes the answer is no, or at least other games are more compelling.

Changing Behavior

When people experienced need frustration–and subsequently changed their expectations for what would happen in future play—this caused them to change their behavior in a few different ways. If need frustration was mild, players might do something different in-game, perhaps going to a different area, or using a different setup to make the obstacle easier. When need frustration was stronger or more frequent, however, players would disengage in one form or another. This player decided to disengage by playing less and less frequently:

My friends would ask me to come play [Counter Strike] with them. I’d be like, ‘please don’t make me do this, I don’t want to play this game.’ And they would keep asking, and then like, you know, I would try one more time, and then get destroyed again, right. […] And like that- the length of time between, you know, me refusing to and me saying `yes, okay, I’ll play one more time’ gets longer and longer, until I just don’t play again.

And of course, in the most serious cases, players would simply quit the game entirely:

[In Zuma] you’re shooting bubbles […] and it’s just coming so quickly that you can’t do it. And I remember being super frustrated at that. […] You know, it shouldn’t be that hard. But yeah, that was one I had to put down and not pick up again because I just- it made me feel incapable. A failure.

Conclusion

Need frustration is a common and impactful experience in video games, and players report that it closely relates to their decisions of when to quit. In fact, one of the key hypotheses that this study led us to is that the difference between “good” and “bad” frustration is the presence or absence of need frustration. In other words, the reason that Dark Souls, for example, is so frustrating but still motivating is because it isn’t undermining players’ sense of autonomy, competence, or relatedness—players still have the opportunity to choose where to go and how to approach an enemy, can see that they’re getting better and learning enemies’ attack patterns as they practice, and feel connected to the world they’re in. The game is frustrating, but not need-frustrating. On the other hand, bad frustration—for example, when a game is so luck-driven that people perceive it as unfair because their actions have no effect on the outcome—is need-frustrating.

On a more personal note, this paper is one of the more difficult studies I’ve conducted, and I’m thrilled it’s finally out in the world. I encourage people to go check out the full paper—for non-academics, you can ignore most of the intro/method/discussion bit, and just focus on the results section with the various quotes. As always, if you have any comments/questions/feedback, please do reach out!

-

I wrote a while back in more detail about what exactly the 3 basic needs in self-determination theory are, and perhaps more importantly, what they’re not. You can find that post here. ↩︎