Losing the battle between productivity and learning for learning's sake

Some reflections and strategies for spending less time doing, and more time learning—or at least doing both at the same time.

Putting Learning on the Back Burner

One of my biggest regrets of my PhD has been transitioning too quickly from a mentality focused on learning, to one focused on outputs. Once I published my first paper and realized “oh, I can do this”, suddenly everything that wasn’t in service of an upcoming publication or similar output started to feel like at best a distraction, and at worst a waste of time. In fact, my outlooks has deteriorated to the extent that learning new research-related things sometimes feels like a hobby rather than an integral part of my work. (You’ll catch me on weekends listening to Quantitude, a highly pedagogical podcast about quantitative methods—to be fair, they do spend half of each episode making dad jokes, but I can safely say I’ve learned as much from them as I have from any stats textbook).

Two crucial caveats here: 1) I fully recognize how problematic this mindset is, and that researchers should be evaluated on much more than the sum quantity of their outputs, and 2) I’m exaggerating a bit for dramatic effect—I do certainly learn a lot during my actual work time. But the reality is, in a environment where every career move feels precarious, and the currency of your advancement is publications, there are legitimate reasons to be laser focused on those outputs and put learning on the back burner, and that’s something I regularly find myself falling victim to.

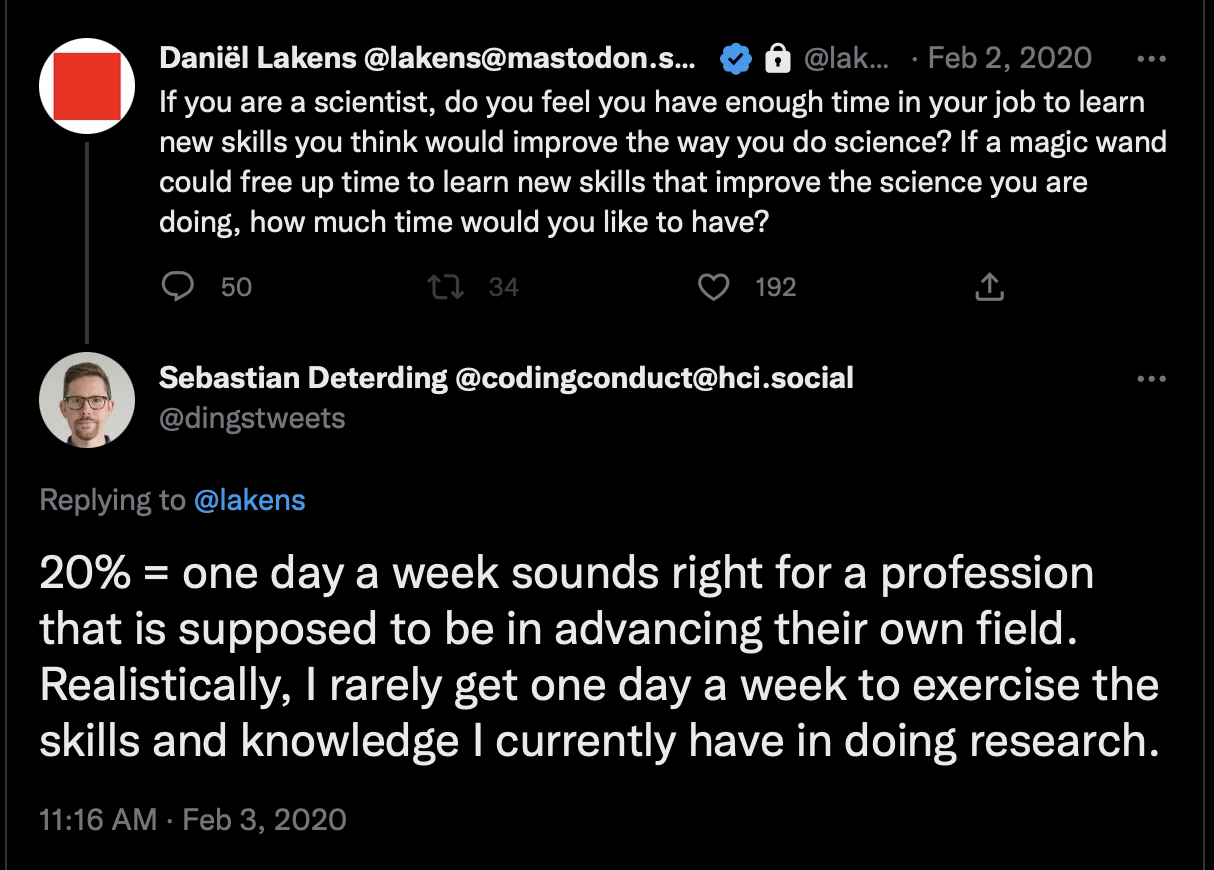

It sounds like I’m not alone, either. A while back, Daniel Lakens asked researchers how much time they’d like to have for learning new skills. The model response seemed to be approximately 1 day a week, but few people found that they were able to achieve this. My supervisor, Sebastian Deterding, described an even more grim reality in the replies (see image). How depressing is that, that our profession leaves hardly any time for even applying hard-(l)earned skills, much less learning for learning’s sake?

Let me illustrate with an example from my own experience. My math background is quite poor; after finishing calculus in high school, I pivoted towards non-quantitative social science topics for my bachelor, and therefore have had hardly any formal math training since. I have more or less learned to mimic what good statisticians in my field do in a given situation, and can usually understand the general insight behind what a statistical model is trying to do and where it can go wrong, but my understanding of what’s happening under the hood can be really quite poor.

So, I tell myself “I’m going to go learn some linear algebra”. At the moment, I have minimal responsibilities aside from my thesis and the luxury of being able—at least on paper—to go do exactly that. But psychologically, I find it very difficult. Pragmatically, only after every other “to-do” on my list is completed do I feel like I can justify some dedicated learning time. But inevitably, this time will become fragmented by incoming emails, tasks, or simply ideas for work that might contribute more directly to my career progression. This feeling, that learning ends up being the lowest of my priorities, is exacerbated by the perception that the thing I’d like to learn about is particularly new or difficult. When I have finally cleared the to-do list enough to sit down and study some linear algebra, I find myself discouraged at my rate of progress—compared to the 8+ hours per week I dedicated to learning new things during my bachelor (combined with some rapidly decaying neural plasticity), learning enough to fully grasp the applications of the math I’m interested in (quantitative methods papers, codebases, etc) feels insurmountable.1

Similar patterns play out with other things I’d like to learn, not just in my work but in my daily life (looking at you, oft-neglected keyboard in the living room corner). At the ripe age of 28, I worry that the period of my life in which I could devote substantial time to learning for learning’s sake was all too short. And frankly, if I’d known what I know now, I’d probably have spent it differently.2

I doubt I need to convince you of the long-term benefit of learning for learning’s sake, both for one’s general well-being and for one’s professional development. But even as someone who consciously tries to place value on intellectual and personal growth, I find my tangible short-term interests more compelling than my ethereal long-term ones.

What to do?

You’ll be disappointed (if unsurprised) to learn that I do not have any silver bullet solutions to this problem, neither for myself nor for others. However, describing my problems in a dark monospace RStudio window always seems to help me work through some potential ideas. Let’s discuss a few.

1. Book your own calendar

My girlfriend, whose calendar is about 50% meetings on any given day, is a huge proponent of booking out one’s own calendar. Blocking out a portion of a particular day—perhaps the same slot every week—with the express intention of sitting down to learn something new and not-necessarily-useful not only helps you guard that time, but also helps you give yourself psychological permission to actually do it. Start small—put an event in your calendar for one hour a week, maybe even less, at a time of day when you’re normally cognitively active. Habit formation research is clear about the importance of starting with something incredibly small and easy. In my case, this might be watching a 3 Blue 1 Brown video for 20 minutes. Setting such a low bar gives you with the feeling of accomplishment from having completed your goal, and often, you’ll find yourself motivated to continue.

2. Pursue teaching and mentorship

I briefly talked about (reverse) mentorship in another blog post, and this strikes me as one of the best ways to integrate learning into one’s everyday work. As they say, if you can’t explain something simply, you don’t understand it well enough. I’ve learned a ton from running workshops on open research—both from the required preparation and reading, and from engaging with participants. This strategy works best if you’re developing new content (and in fact really only works at all if you’re updating your content and not giving word-for-word the same lecture for the 150th time.) Nonetheless, I try myself to find opportunities to commit to instruct others in a topic you are not yet fully comfortable or fluent in, and recommend that others do the same. This can be nerve-wracking, but 1) you’re probably underestimating how much your existing expertise will help you develop in this new area (and/or overestimating others’ knowledge), 2) people are generally very understanding if you’re honest about what you don’t know, and 3) they’ll likely be grateful for having learned anything at all. Lab meetings, reading groups, scicomm opportunities like The Conversation, and teaching assistantships in new topics can all be entry points for adopting these kinds of roles.

3. Seek out Safety Mode collaborations

As hinted at above, I’m the kind of person who needs a project to motivate learning. I have a hard time playing around with a toy problem, or something in the abstract—I learn best when confronted with a task whose outcome matters in some way. For the sake of illustration, let’s consider three broad ways that research projects can operate, which I’ll call Superhero Mode, Specialist Mode, and Safety Net Mode.

-

Superhero Mode: One person is the end-all and be-all of the project. Recognizing that academic careers push everyone to be a jack-of-all-trades, master-of-everything—a hugely unfair and counterproductive expectation—the lead author does the vast majority of the heavy lifting, even when the tasks are beyond their current capabilities. Common in PhD students, especially with more hands-off supervisors. When important skills are missing, this results in the feeling of being “thrown in the deep end”.

-

Specialist Mode: Each member of a team contributes in a specific role. This is often pitched as the ideal collaboration structure, as it maximizes output per unit of total effort. For example, in each new project we begin in one of my lab groups, we have an immediate idea of everyone’s role based on their skillset. Each collaborator’s strengths are largely complementary (lit review, data collection, statistical methods, open science practices, etc), allowing us to conduct and write-up relatively sound research in a relatively short period of time. However, while it’s important to exercise one’s capabilities and feel like you can meaningfully contribute without it demanding too much of you, it’s equally important to recognize that Specialist Mode projects may not further one’s growth as a researcher very much. Specialist Mode collaborations are opportunities to get rewarded for the knowledge that you already have, but don’t always help people expand beyond that.

-

Safety Net Mode: Each member of the team brings their own type of expertise, but the team divides responsibilities such that people who are less capable in a particular area complete those tasks, and have the more experienced team member to provide oversight. This allows people to push themselves to learn challenging new things, but 1) with a purpose, and 2) with a safety net. Let’s be clear, having people do tasks that they aren’t as good at is not the most efficient way to run a project. It requires very clear expectation setting, and the kind of project that is not urgent, or career-defining, or conducted in collaboration with people with whom you don’t yet feel comfortable being vulnerable. But

Superhero Mode was where I started my PhD. My supervisors had some expertise in what I wanted to do, but were less familiar with other areas, and as I result I spent a lot of time off on my own learning—a valuable experience, but not one without some stress. As I got more competent in my areas of interest and strengthened my collaboration networks, I moved into more Specialist Mode research, where I was recruited (or recruited others) to complement each other’s skills.

In this 4th year of my PhD, however, I’ve been trying to seek out more Safety Net Mode collaborations. For example, I recently learned how better to simulate power analyses for structural equation models by volunteering for that role, knowing that there was an SEM expert in the background to catch me if and when I made mistakes. This shift in mindset in what I try to get from (some) collaborations has been highly valuable, and given me some space to feel that I have time to learn, while still producing something to the benefit of my career (and hopefully our knowledge about some phenomenon—I don’t mean to sound too instrumental in my view towards research!)

Safety Net Mode needs to be deployed with care. For example, in a recent project, I wanted to try out a Bayesian analysis (I’m currently a wannabe Bayesian, hoping to graduate to Bayesian-in-training at some point). However, because the other collaborators had less of a background in Bayesian tests than I did, the safety net was weak, and the risk to the quality of the research, or at least the time needed to learn the skills, was too high. Safety Net Mode won’t be right for every project, but it’s an option worth keeping in mind as you distribute roles.

Summing up

I hope this has been valuable for some of you. I think it’s vital to reflect upon how much time we spent learning, how much time we’d like to spend learning, and how best to integrate that alongside the other demands of our work. To sum up, I’d give the following advice to others, particularly PhD students:

- Cherish the time you have for pure learning, and know that this will contribute to your productivity eventually without it needing to do so immediately

- If you’re struggling to dedicate time for learning new things, book your own calendar and hold yourself accountable (for example, by having a meeting with someone else who does the same thing to swap insights)

- Seek out teaching/mentorship opportunities, and use them as learning opportunities

- Seek out Safety Mode collaborations, and consider using tools like the CReDiT taxonomy for distributing tasks with careful consideration of each collaborator’s strengths and weaknesses

-

It doesn’t help that the size of the research literature continues to balloon. With the number of papers being published, I often feel that I barely have bandwidth to stay on top of papers in my narrow subfield of psychology of video games and wellbeing, much less read more widely. ↩︎

-

I have a longstanding worry about the ratio of methodologists to domain experts in my area of research. At times, I feel like I could teach someone with a strong quant background all of the domain expertise needed to understand my research area in just a few weeks. Meanwhile, for someone with no quantitative background (i.e., me) to learn the foundations necessary to understand, much less contribute to, the advanced quantitative methods literature, it would require nothing short of an entire re-education. In other words, some learned skills seem to do a better job of scaffolding for future learning than others. ↩︎