Research Impact, and the Quicksand of Gaming Disorder

Some thoughts about a tension I’ve noticed in finding my research direction.

As most of my PhD cohort can tell you, I think a lot about the impact of my research. It’s kind of crippling, actually. I get paid a pretty paltry sum (although I’m lucky enough to be better off than many other PhD students), and even though I’m fully aware that governments spend vastly larger sums of money on vastly dumber things than my research, I still can’t shake the feeling that taxpayers are keeping me afloat right now, and they deserve something tangible in return. This has become even more glaring when you think about the impact that the PhD students working on the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine had. The social sciences just can’t compete with that.

Part of this anxiety about impact is a reflection of how I arrived in the field of games psychology. My undergraduate and master were in linguistics, and while I adored the content of what I was learning, I slowly began to feel that it was all rather useless. The “pure” linguists looked down at the computational linguists for not actually understanding the structure of language and instead reducing it down to probabilities (queue discussion about the sentence colorless green dreams sleep furiously)—while the buried elitist in me still believes that to a certain extent, the other side of the story is that computational linguistics were getting things done. It was easy to see the impact of their research on the world; we interacted with it every time we used Siri, or Google Translate, or any one of a million other things. (As an aside, I’m thrilled to be able to use automated translation for an upcoming interview study I’m doing. Thanks, computational linguists.)

But the feeling that my particular branch of linguistics—the phonetics of second language acquisition—had no real path to impacting everyday people was precisely what led me, with some meandering, to my current work. I found myself reading through some of the most prominent games-related research, much of which to this day is about violent games and aggression, and I thought to myself “these people don’t really seem to understand how games work, but their research is shaping public opinion all over the world. Maybe I can help make this a little better.”

This is where I hit my first challenge. I’m of the opinion that games can be—and most of the time, are—a powerful force for good. I think that play is a fundamental part of what it means to be human, I think games can be as expressive and artistic as any other medium you hold them up against, and I think the communities that form around gaming, at their best, add a tremendous amount of richness and connection to people’s lives. But to really build that argument, it felt like I needed first to disprove or qualify the reverse; I needed to address the often persuasive rhetoric that games are inherently harmful.

At my first Christmas at home after beginning my PhD, my sister-in-law asked me “so, have you found any evidence?” “Evidence for what?” I asked, confused. “That violent games lead to anti-social behavior.” She was concerned—and completely understandably so—that because all her sons’ friends were playing Fortnite, she had to either choose between depriving them of interaction with their friend group or exposing them to something that might negatively affect their development.

I managed to avoid conducting research on violent video games, largely because—although I still regularly get notifications about new publications on that topic—I’m of the opinion that the evidence is clear: the effects are unreliable, the experiments that generated them do not generalize, and even when effects may exist, they’re not large enough to be societally meaningful.

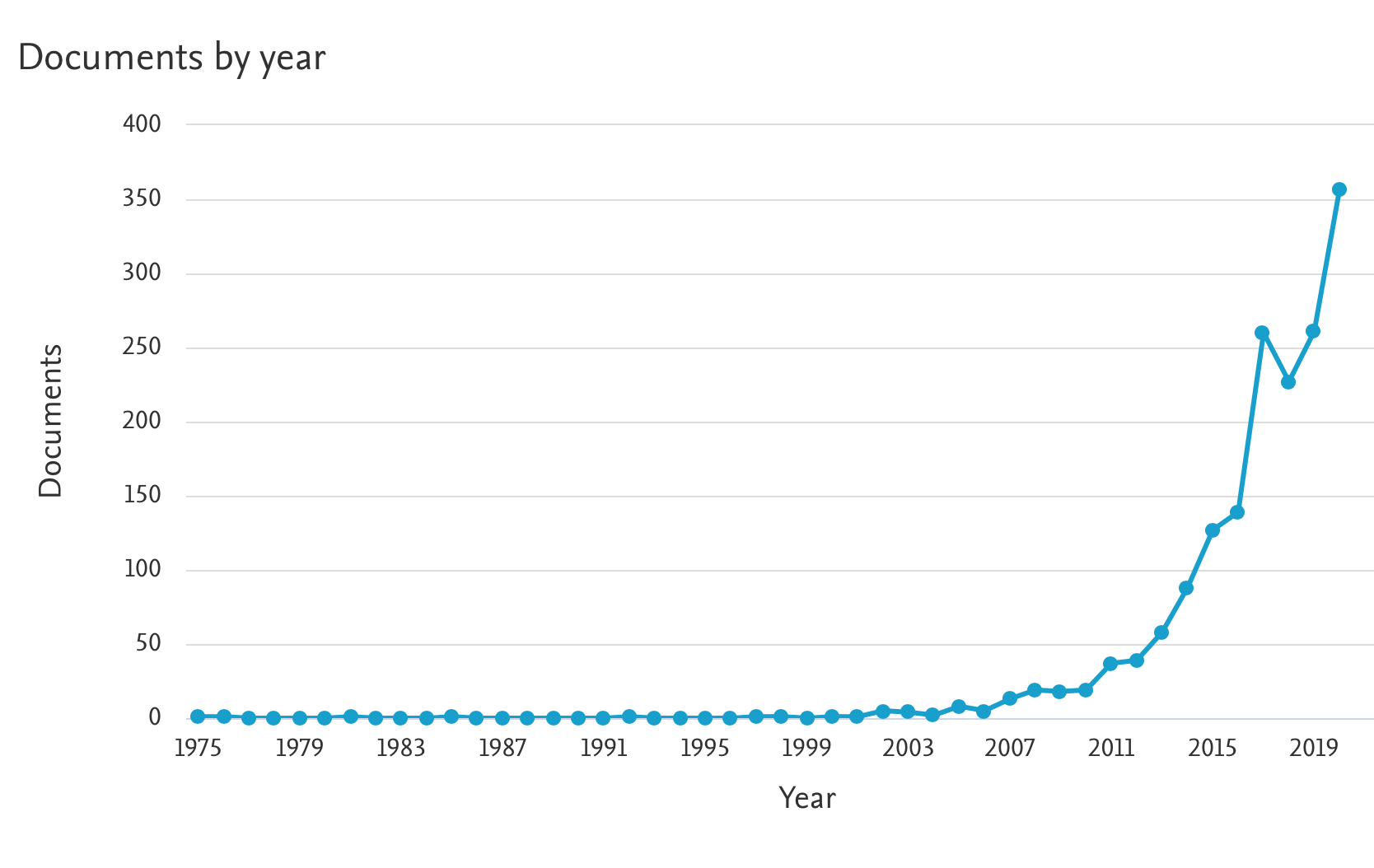

However, I did not manage to avoid the great game debate number two: (internet) gaming disorder. This is a topic that has been exploding in recent years, with no sign of slowing. And again, I think it is a topic that a lot of researchers misunderstand. I’m interested in motivation, but as soon as I ventured into that literature about why people play, you inevitably run up against the people asking why people play so much that it results in negative consequences to their life. I felt gaming disorder pulling at me like quicksand. When people asked me what I do, often their first questions were about gaming “addiction”, and I felt obligated to answer them. I found it easier to justify the impact of my work when it was related to specific people with a specific set of problems than when it was about something less concrete like “helping parents and players to manage their game use in a healthy way” or “informing designers about the potential motivational impacts of their design decisions”. These latter points sound good, and I do still believe that they are true and valuable, but the material steps I need to take to realize them are less obvious to me.

The crux of my point is that it seems so much easier to justify work that helps stop something concrete and harmful than work that might create something positive, or make a positive thing even more positive. I suppose positive psychology has understood this for a long time, given that it was developed in response to the observation that psychology to that point had focused almost entirely on psychopathologies—that is, people with mental health conditions. Positive psychology wanted to be the other side of that coin, asking not how we can be free of disease, but actively thrive.

I haven’t solved this problem, and am currently sort of walking along the neutral ground. I’m using a theory (self-determination theory) that seeks to explain why games are so intrinsically motivating, and how that quality of motivation can contribute to well-being and thriving; however, I’m applying the less-understood flip side of that coin to better understand the rarer conditions in which games may undermine well-being. I still want to explore why games can be so valuable in people’s lives, but I’m doing it by intellectual litotes, by putting clearer constraints on the conditions under which the harmful relationships with games do exist.

A syntactician friend of mine made me feel a little better about all this, arguing that even in the absence of a tangible impact on the general population, the things we research are inherently interesting, and might be thought of almost as leisure activities—were people to have more time and cognitive energy, perhaps in a 15-hour workweek world, they would engage with these topics and find that them enriching. If nothing else, I hope my descendants will one day live in a world where this is true and where all kinds of people can enrich their lives by tinkering with games and motivation to create a more playful world, and I hope my research will be one tiny building block as they do this. It may be a few decades or centuries away, but perhaps that’s all the impact I need.